Lecture 3 Market Access

3.1 Pareto Criterion revisited

Let’s review what we learnt about the Pareto Criterion in Section 1.1 above. Any trade that makes someone better-off without making someone else worse-off is a Pareto improvement.

An intervention that makes some people better off without making anyone worse off is called a Pareto improvement.

Pareto efficiency thus is defined as a outcome where no one could be made better-off without making anyone else worse-off.

Pareto efficiency situations are one where you cannot make anyone better-off without making anyone worse off.

Initiating a process of development in an area or a country requires either an entity like the government or a community identifying and solving the problem or it requires initiating a process that allows people to access markets. The two approaches are distinct. The first approach requires an individual or an institution diagnosing the problems that have impeded the region or country from developing economically. Put another way, it is a centralised approach, i.e., a central authority has to identify the problem and solve it. Conversely, the second approach is a market-based or de-centralised approach and does not require an individual or any particular entity to take an initiative. It is the nature of the markets that they allocate resources through bilateral trading in a decentralised way without the intervention of an entity.

We can evaluate the two approaches in terms of the Pareto criterion. To reach the state of Pareto efficiency through the first approach, we would require the government or any other entity to acquire information about how each individual value goods and service in the society. It should obvious that it would be an extremely resource intensive exercise and a developing country does not have the resources to undertake such an exercise. In fact, such an exercise would strain the public finances of even the most prosperous nations in the world today.

Conversely, the government or the entity could try to initiate a market based approach. The advantage of such an approach is that once the market starts working, it allocates the resources through bilateral trade. There is no need for a central authority to acquire information about how people value goods and services and how the allocation should be done. If individuals are allowed to participate in the market without any restriction, then all they have to do is decide whether they have to accept or reject the trade that is on offer. It does not even require an individual to be familiar with their own preferences. All it requires off them is to know whether they would accept or reject the offer of trade in front of them. If we allow the market to proceed without any limits at all, at some point all the potential trades that people can possibly engage in would have been undertaken. At this point no one would have any trades left to make and everyone would simply return back home.

This is the essence of Adam Smith’s original insight. It allows us to understand the potential of markets to allocate resources within a society. Adam Smith argued that once all the trades have taken place, the market outcome reached would be Pareto efficient, i.e., once all the market trades have taken place, there is no scope for making anyone better-off without making anyone worse-off.

While Adam Smith’s insight was revolutionary in the age of feudalism and mercantilism, fully appreciating Adam Smith’s insight in today’s context where most societies tend to be market based requires understanding the conditions under which market obtain the Pareto efficient outcome. This only happens if there are not externalities, no information problem, no strategic interaction between buyers and sellers and no scale issues. By addressing these issues, the government can facilitate the functioning of the markets.

3.1.2 Markets and Efficiency

Without markets, people often live in a state of autarky. That is, the produce everything they need to consume. Markets allow people to specialise introducing things that they are good at and then using the proceeds from the sale to buy whatever they need. Thus, market has the potential of making everyone better off. Markets facilitate trades between people and once all the trades have taken place the outcome is Pareto efficient. If the outcome was not Pareto efficient, then that would mean that you could make somebody better off without making any body worse off. This implies that there exists a trade that makes two or more parties off has not yet taken place. Hence once all the true potential trades that make people better off have been undertaken the outcome has to be Pareto efficient. The problem that relate as in developing countries face is that there is very limited access to market.

It is useful to think about Adam Smith’s insight about markets. Adam Smith was the first want to realise that well-functioning markets are Pareto efficient. That is all mutually beneficial trades are undertaken and no trades than can make someone better off without making anyone worse off are left unexploited. He was also able to pin point the characteristics that lead to a well-functioning markets that attains a Pareto efficient outcome. These characteristics are as follows:

No one has market power: No entity should have an ability to influence the market. Each entity that participate in the market either as a buyer or a seller should be should be too small to influence the outcome of the market on their own.

No information problem between the buyer and the seller: The buyer should how old information they need to attribute value to a good so that they know where did they would like to buy it or not. If there is some information like the quality of the good that is hidden from the buyer, then the buyer may not undertake the trade. If the information problem is persistent, then and it could lead to the market collapsing. Health and safety laws are designed to convey information about the quality of the good to the consumer in order to facilitate the markets.

No externalities: there should be no external effect of the trade on a third party that is not involved in the trade. If there is an external effect on the third party, then a particular trade may make the two parties and hold on the train better off but make a third-party worse off. It should be apparent that this would not be a Pareto efficient outcome.

3.2 Kerala Fish Market

Fish markets are extremely interesting in terms of how they operate. Fish as a product is best consumed fresh. It can be frozen, but frozen fish loses flavour and people tend to prefer fresh fish over frozen fish. Further, freezing fish is capital intensive. The dynamics of fish markets is really interesting across the world.

Graddy (2006) and Graddy (1995) contain a fascinating discussion on the operation of the Fulton Fish Market, one of the world’s biggest fish market located in the New York. A discussion of the papers is contained in the Section 3.5 below.

In developing countries, where is capital is comparatively scarce, fresh fish markets open pop up along the coastal areas. Jensen (2007) studied of 15 fish markets along the 225 km Northern coast of Kerala. The aim of the study was to examine the operation of the fish markets. There are pertinent questions like what was the price of fish in each market and does the price vary from market to market. Further, do all the markets clear or are there markets with excess supply or excess demand.

The fisherman along the Kerala coast take their boats out early in the morning. Once they are done for the day, they usually take their catch of the day to one of the 15 fish markets along the coast where they sell it to the fish merchants, who in turn sell it to the customers. The fishermen have a key choice to make once they have caught their load for the day. The key choice is which market should they go to sell their catch. Obviously, they would like to go the market where they would get the best price. The problem is the knowledge of the price at any point in time was difficult to obtain before the advent of mobile phones.

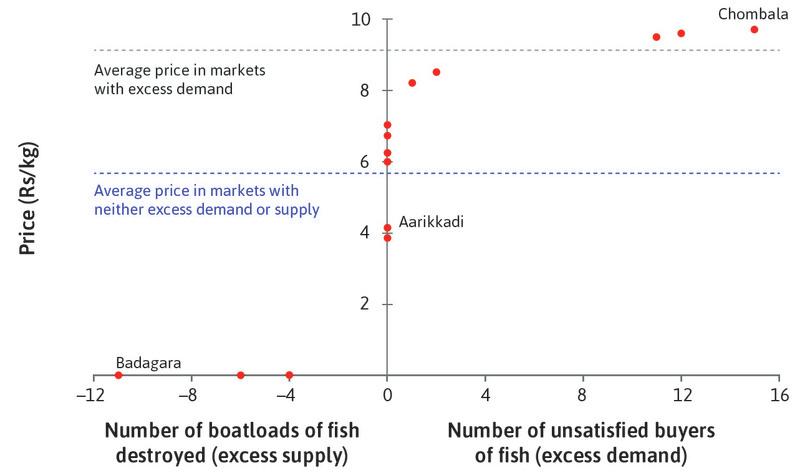

Fig: Excess demand and excess supply

Jensen (2007) found that the fish prices were high and fisherman’s profits were low due to wastage and bargaining power of fish merchants who bought from the fisherman and sold to the customers. For instance, on 14th January 1997, 11 boats jettisoned their catch due to excess supply in the Badagara fish market and 15 buyers left unable to purchase fish at any price in the Chombala fish market.

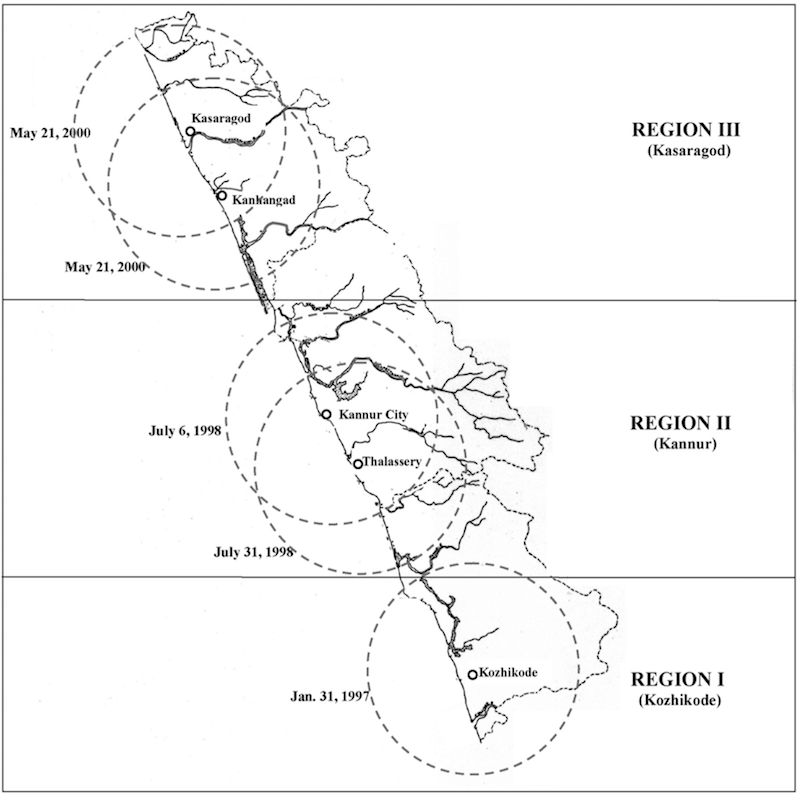

The northern Kerala coastline got mobile phone coverage in 1997. The mobile phones coverage was rolled out sequentially in the three areas. We can see the three regions, i.e., Region I, II and III in the figure on the right.

Fig: Mobile phone coverage

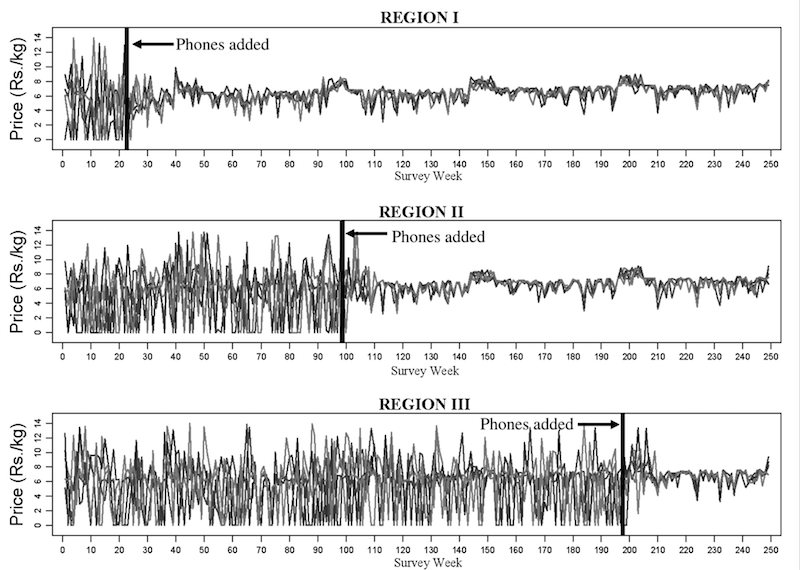

If you look at the price data from the markets in three region we find that there was a striking drop in price volatility of daily prices as the mobile phones are rolled in to a particular area. The drop in volatility of price lead to both the fisherman and consumers being better off. Once an area gets the mobile phone coverage, the paper finds that both consumer prices drop and the fisherman’s profits increase.

Jensen (2007) documents how it reduced wastage of fish, led to markets clearing and decreased volatility of price. Further, fisherman’s profits went up by 8% and consumer prices decreased by 4%. Thus, introduction of mobile phones in Kerala made the fish market more efficient. That is, rolling out mobile phones across the Kerala coastline can be considered a Pareto Improvement.

Fig: Market price of fish

Once mobile phones for introduced, the transaction cost14 in the market has decreased. In the fish market, the cost of acquiring information was a large part of the the transaction cost. The transaction cost dropped because of the introduction of a public good, i.e., the mobile phone network. It is public good that would have been too expensive for the fisherman to provide for themselves because of the increasing returns to scale. It was a public good that was facilitated by government policy. The government policy created a regulatory framework and gave the private mobile phone companies the incentive to invest in providing mobile phone coverage in that area.

3.2.1 Mobile phones as Public Goods

Mobile phone network is public good that has a very high increasing returns to scale. The scale here is the number of people who have access to mobile phones. If the number is small, the benefits are more limited. As the numbers increase, the benefits increase too. If we start from a very small scale, say one-tenth of the population being covered by mobile phones and double the network, so that one-fifth of the population is covered, it is intuitive that the pecuniary and non-pecuniary benefits accrued will be more than doubled. This will keep happening till the full population is covered.

Mobile phones have two components in its provisions. The first one is establishing the network. This entails creating a regulatory framework within which mobile operators operate. Only once this regulatory framework is established and mobile phone operators obtain their licence to operate that they start making their private investments in building mobile phone base stations that facilitate mobile phone communication. The private investment (private capital formation) only happens once the public good (public capital formation) is in place.

3.2.2 Infrastructure provision and markets

Jensen (2007) illustrates the link between infrastructure provision and markets. It is good example of how infrastructure provision can facilitate markets to function properly, allowing people living in the area to specialise in producing things that they have a competitive advantage in and trading it with each other through.

Though it is important to understand how far we can generalise from Jensen (2007). When the fishermen was the turning from sea, they could choose to go to any market because of the nature of the space. They could choose to head to any particular market in a straight line over water. This is not true in landlocked areas. Inland lock areas the markets you can go to is determined by the transport network. This is one of the reasons why so the earliest markets and trading centres in the world developed next to water bodies.

Water bodies are crucial to development of markets in early urban agglomerations or markets. Urban agglomerations like like London, Venice, Banaras, New York and Tokyo developed next to the water bodies. Water bodies as natural automated surfaces15 on which people and cargo can move easily. Water bodies like Suez Canal and Erie Canal have played a key role in facilitating trade. The problem we have when it comes to developing areas is that large parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America are landlocked with very little access to automated surfaces that facilitate markets and trade.

Opened on October 26, 1825, the Erie Canal ran 584 km from Hudson River to Lake Erie. It was faster than carts pulled by draft animals and cut transport costs by about 95%.

Well-functioning markets are crucial for development. Railway and roads can play the same role in creating market in the absence of water bodies. The problem is that transport network have a very high increasing returns to scale. Building a transport network that reduces the cost of moving goods and services and facilitate the flow of price information requires upfront fiscal capacity because they are non-rival and non-excludable

Fiscal capacity: a country’s capacity to tax the economic activity and spend it in a productive way on public capital so that it creates economic activity.

The transport networks becomes key when it comes to facilitating development in inland locked areas of the world. In the next two chapters we will see how the road building in Kenya and railways construction in India during the Raj played a key part facilitating markets and engendering development in the rural parts of these countries.

3.3 Goods Market

Without exception, every country has markets where there are transaction between the sellers and buyers. Market economies are the ones where market based transaction dominate the non-market transactions. Non-market transactions are where either a person obtains a good (or service16) through relationships or from the government. These are more complicated transaction. A good received from a someone one has a relationship with is part of an open-ended transaction is one that carries a implicit obligation to respond at a later stage. With government, a person has the obligation to pay taxes and receives public goods that government provides in return. We will return to these non-market transactions in the subsequent chapters.

In all economies there are two kinds of goods that are transacted. The first type of goods are consumptions goods, i.e., goods that satisfy a human desire. Examples of these are most things you would find on a grocery store shelf. The second of good are capital goods, i.e., goods that are used to produce other goods. These are goods like screwdriver, cranes, conveyor belt and range of other machinery.

We have two kinds of firms in the economy. Ones that produce capital goods and ones that produce consumption goods. The market for consumption goods is where households buy consumption goods from firms that produce consumption goods. The market for capital goods is different. The firms that produce consumption goods need capital goods to produce consumption good. They buy them from firms that produce capital goods. The market for capital goods is one where firms transact with each other.

The act of buying capital goods from firms that produce capital goods is called gross investment. Gross investment serves two purposes. The first kind of investment is where a firm reverse the ageing process of capital goods it already have. That is it takes care of wear and tear of the machines it has been using. This kind of investment is called depreciation. The second kind of investment is where the firm increases its production capacity. This is called net investment.17

Goods market in the economy has a slightly different characteristic than each individual goods market. If the demand for milk increases in the economy, either the price of milk rises or the supply of milk rises. For the supply of milk to rise, either the milk producers have to induce the workers to work harder or hire new workers. Alternatively, they could increase production capacity by installing additional machines. While these possibilities exist for one market in the economy, these possibilities do not exist for the economy as a whole. This is because when the milk producers hire more workers, they induce them way from other industries. For number of workers in milk industry to increase, the number of workers in another industry has to decrease. Similarly, milk industry can increase production capacity only if the production capacity decreases in another industry. If the demand for goods across the economy increases, then given the total capital and labour in the economy, it is not possible for goods supply to increase. The goods supply at the aggregate level would remain the same and the prices across the board would have to rise. The idea of the macroeconomic balance is one where the supply and demand are balanced, i.e., the prices are entirely flexible and ensure that supply of goods is equal to demand for goods. While supply and demand can be unbalanced in the short-run, these wrinkles get smoothed out over the long run.18 We are looking a economic growth over the course of the long-run and thus macroeconomic balance can be taken as given when we do so.

3.4 Public Goods

Public goods of two characteristics. They are non-rival and non-excludable.

When a good is rival, its consumption by one person reduces the amount other people can consume. Non-rival goods are goods where consumption by one person does not reduce the amount other people can consume. Examples include air, water, aroma etc.

A good is excludable when people can be excluded from benefiting from it, either naturally or through some contrived process. A good is non-excludable when people cannot be excluded from benefiting from it.

| Rivalous | Non-Rival | |

|---|---|---|

| Excludable | Private goods | Club goods |

| e.g., food and Housing | e.g., French motorways, Apps, Gym, Clubs | |

| Non-excludable | Common-pool resource | Pure public goods |

| e.g., like ponds, sea fish and the commons | e.g., UK motorways, National defence |

3.4.1 Property Rights

What are property rights?how are property rights enforced

Who owns property rights over natural resources?

right to pollute

right to have a clean environment

E.g. noise

right to make noise

right to pin drop silence

Conditions for markets to function properly

Private property: people have the right to buy and sell things

Either social norms are such that property rights are universally respected

Or institutions like the government enforces property rights through its judicial system

Ability to write complete and enforceable contracts that can be enforced in a court of law

3.5 Fulton Fish Market

Graddy (1995) collected data on whiting transaction in in New York’s Fulton Fish Market during the 1991-92 period with the objective of examining whether the law of one price hold for the whiting transactions. Fulton Fish Market remains one of the largest wholesale fish markets in the world (Graddy 2006). It is a wholesale market where the restaurant and fish shops owners in the New York area buy their fish. The buyers are well informed and buy fish in large quantities. On the face of it, the Fulton fish market fulfilled all the conditions of a highly competitive market when Kathryn Graddy collected her data on whiting fish transactions in the 1991-92 period. At that point in time, there were about 60 fish sellers with about 35 sellers operating actively. Only 6 sellers dealt with whiting.

There were two main groups of buyers, an Asian group and a white group. Graddy (1995) found Asian buyers paid 7% less for whiting as compared to the white buyers after controlling for quality. Her analysis shows that it was because the Asians were more coordinated as a social group and were able to sanction or boycott a dealer collectively who they felt had cheated them. Conversely, there was no such coordination amongst the white buyers. Asians were able to pay lower prices because they were operating as a social group. The mystery is why didn’t some sellers exploit the arbitrage opportunities by offering white buyers lower prices. To understand this, we will have to understand the power dynamics operating in the market space.

Graddy (1995) cites numerous New York Times articles that document how the mafia controlled the street parking around the Fulton fish market (Raab 1996, 1995a, 1995b). The control of the street parking allowed them to control the loading operation in the Fulton fish market.

A seller who wanted to operate in the Fulton fish market was required to have the approval of the mafia. Presumably, the approval of the mafia came with its own cost. The mafia’s hold over the operations of the market kept a check on the entry of new fish sellers in the market. It ensured that the arbitrage opportunity in the Fulton fish market was not exploited due to the high cost of entry. The mafia was able to exert power over the operations of the Fulton fish market by exerting power on the space that surrounded it.

Individuals experienced the market-space through their own social space. While the Asian buyers were able to create and maintain their social space that was superimposed on the market-space, no such social space existed for the white buyers. The Asian buyers were able to use leverage their social space to their advantage. The mafia was able to create its own social space and use it to exert power over the operations of the Fulton fish market. It is interesting to note that the only reason Asian buyers were able to use the social space to their advantage was due to the fact that the mafia was using the social space to its own advantage. In this way, the power exerted by social spaces on the markers undercuts decentralising property of the market.

A decentralised market dissipates power and creates a power vacuum, creating lucrative opportunities for social groups to exert power over the market-space by fragmenting along the lines of social space.

This dynamic process of market-space fragmentation is an entirely endogenous process, i.e., any market decentralised market creates an opportunity for social groups the fragments the market-space in order to take advantage of it. The market-space in Fulton fish market got fragmented into the respective social spaces of Asian and White buyers due to the power exerted by the Mafia on the space around Fulton fish market.

The authorities in New York city administration that were responsbile for the Fulton Fish market conceived it as a space for the market to operate freely, i.e., any seller with a shop in the market could sell to any buyer who was willing to buy. Yet, this was at variance with the way the Mafia conceived the space. They conceived it as a space that would work in their interest. They exerted power over the space by dominating the street parking around the fish market and ensuring that only they would unload the fish brought to the market. The Asian and White buyers perceived the space in different ways. While the white buyers perceived it as a decentralised market, the Asian buyers conceived it as a place where they could benefit bargain by bargaining collective. The market worked because the way the Mafia and the Asian buyers conceived the space did not mutually interfere. Hence, the market worked in the sense in which Hayek (1937) had conceptualised it. What is fascinating is that different groups had different lived experiences in the same same space. Creating a market-space that facilitates the functioning of a decentralised market requires conceiving it as decentralised space, ensuring that it is perceived as a decentralised space and people experience or “live in it” as a decentralised space.

3.1.1 Social Surplus

Think about what happens when a person trades something with another individual. A logical person would only trade if they would be better-off with the trade. Similarly, the other person would trade with them only if suits them, i.e., makes them better-off. If either of them are worse-off after the trade, it would be in their interest to not undertake the trade. Hence, if people are logical and free of coercion, they would only trade if they are better off after the trade as compared to their situation if no trade takes place. We can define a notion called social surplus.

Let’s talk at a situation where Angela has a kilogram your bananas with her and Bruno has a kilogram of apples. Angela would experience five units of happiness if she were to consume the kilogram of banana she had in her possession. Bruno Will also experience five units of happiness if you were to consume kilogram of apples he had in his possession. Angela really likes apples and would obtain seven units of happiness if she could consume a kilogram of apples instead. Similarly, Bruno likes bananas and would obtain eight units of happiness if you could consume a kilogram of bananas instead. This is a situation where what Angela and Bruno would prefer to consume what the other person has or what they have in their possession. Thus, they both have a strong incentive to trade with each other.

An individual’s welfare or happiness from the status quo is called the opportunity cost. So, opportunity cost is all the welfare or happen is they would obtain if they forgo an opportunity presented to them. In this case, both Angela and Bruno’s opportunity cost is 5 units of happiness.

Opportunity cost is an individual’s welfare in a status quo situation, i.e., when the person forgoes a new opportunity.

Opportunity cost is it useful metric which allows us to measure the gain an individual obtains from undertaking a new opportunity. It should be obvious that Angela and Bruno would not undertake an opportunity that leads them to up to a situation where they end up with less than five units of happiness.

Let’s think about what we are assuming about Angela and Bruno’s ability to make a decision. We are not requiring Angela and Bruno to make any complicated decisions. All we require here is that what Angela and Bruno use logic when they make decisions. This doesn’t preclude him from being altruistic what subject to temptation. All it requires is that the logic in it compare how happy they would be if they undertake dr need to trade with the status quo situation where they don’t trade. It is useful to note that you’re not requiring Angela and Bruno to be super rational. All that is required of them is an ability to compare the two situations they could potentially find themselves in. We also assume that Angela and Bruno are free to make decisions and are not subject to any coercion.

Let’s say that if Angela and Bruno trade with each other, it would lead them to have 7 and 8 units of happiness respectively. To calculate the social surplus, all we have to do is subtract the total opportunity cost from the total happiness they obtain if they undertake the trade. Angela and Bruno obtain 15 units of happiness if the trade with each other. They don’t need opportunity cost it’s 10 units of happiness. The social surplus in this case is 5 units of happiness.

Social surplus is the gain from trade.

While we have identified that the trade would lead to a social surplus, you have said nothing about how the social surplus would be distributed between Angela and Bruno. How the social surplus will be distributed between the two would depend on their relative bargaining power. Even without knowing anything about the relative bargaining power we can be certain that both Angela and Bruno will not undertake the trade if it makes them worse off. They were only undertake the trade if they both can do better then the opportunity cost. Hence, event without any knowledge of the relative bargaining position, we can confidently say that the trade would only take place if the a board better off from the status quo position.

Let’s not think of a market where there are lots of lots of people with things to trade. They meet each other and show each other what they have to trade. In each case they have to decide whether to undertake the trade of forgo it. After a certain time read read your situation where everyone who could trade would have trades. This is a situation where all the social surplus has been exploited and there are no more trades to be made. We can also say that in this situation, all the possible opportunities of making someone better-off without making someone worse-off have been exploited. There are no opportunities left for Pareto improvement. Hence, the market outcome must be Pareto efficient.

Adam Smith’s insight was that the outcome of a well-functioning markets is also going to be Pareto efficient.

It is important to stop for a moment here and and try to fully absorb Adam Smith insight. It is usually difficult to fully appreciate it because his insight is so deceptively simple. Adam Smith said that a market based allocation process that is entirely decentralised would lead to an outcome that would be Pareto efficient, i.e., an outcome that cannot by definition be improved upon through any mechanism. Decentralised here means that no one person or entity is directing the trade. People are deciding whether to train or not on a bilateral basis without any control, coercion or influence from an external entity with authority. Adam Smith’s inside contains a really interesting observation about human agency. Individuals in the society, when powered to make a decision, can reach and outcome that cannot be bettered by entity with authority. The entity may have some authority to coerce and control, but it does not possess the information required to explore all the opportunities for social surplus. Put another way, even if the society used all the intellectual prowess at its disposal, it would still not be able a find a better way of allocating resources than way market does it.

While Adam Smith’s insight is very useful in showing us the superiority of a market based mechanism, there is a really big caveat that is often missed by market fundamentalist, i.e., people who have a religious belief in the power of the market and are not ready to question under any circumstances. Adam Smith’s insight only holds if its a a well-functioning market. That is, Adam Smith was referring to a very specific kind of market - one that functions properly. It follows that a market that does not functions properly would not lead to a Pareto efficient outcome. We will discuss at length what the criterion are for a market to function properly below.

Let’s use these concepts to discuss a real life market in the section below.